Microscopic life

Our interactive Microscope Exhibit is one of the most popular attractions in the Two Oceans Aquarium’s Skretting Diversity Gallery. Here, children and adults can marvel at the wondrous worlds invisible to the naked eye. A trained staff member, Young Biologist or Aquarium volunteer will introduce you to the world of the minute and microscopic – the tiny tube feet a sea urchin uses to walk, the odd behaviours of the near-microscopic shrimp and a host of amazing sea life collected daily from the shores of Cape Town. Our digital microscope projects magnifications of the subject under examination onto an array of screens so you can see these features in high definition.

Look closer: Strawberry anemones

What is a strawberry anemone?

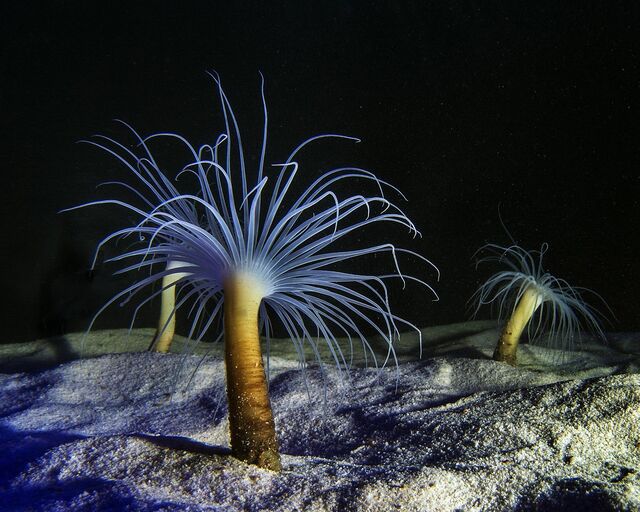

The strawberry anemone, Corynactis californica, is a brightly coloured colonial anthozoan similar to sea anemones and hard corals. They aren’t true anemones, though: strawberry anemones are of the order corallimorpharia, meaning that they look like coral but lack the exoskeleton. These anemones are usually present in a range of red hues, but purple, brown, yellow or almost white colonies can also be found. Strawberry anemones have transparent or white tentacles with bulbous tips that cannot fully retract. Individual anemones are around 2.5 cm tall while colonies can reach widths of 20 m.Habitats and lifestyles

The strawberry anemone feeds on crustaceans, larvae, copepods, and invertebrates. They reproduce asexually and sexually, although they are able to cover more available ground when reproducing asexually. These anemones can live up to 50 m deep on vertical rock walls, or at the bottom of kelp forests.

Look closer: Sea urchins

What is a sea urchin?

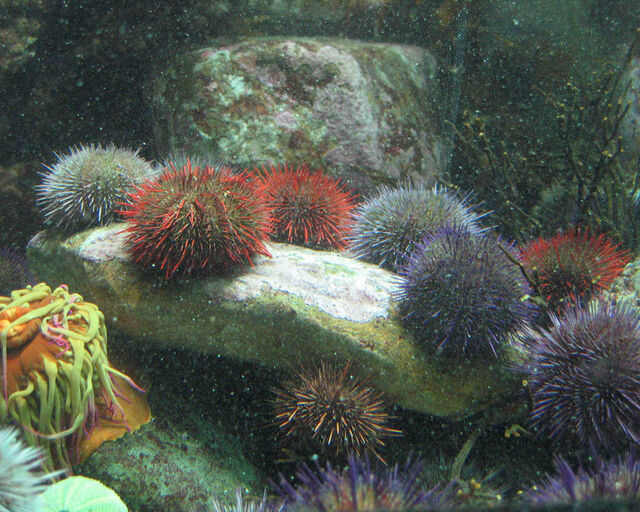

Spikes, or spines, are nature's most resource-efficient armour. No animal epitomises spikes better than the sea urchin - but our microscope reveals that there is more to these "simple" animals than meets the naked eye. Sea urchins are part of the phylum Echinodermata, members of which are recognizable by their radial symmetry and hard, spiny covering or skin.Tiny feet

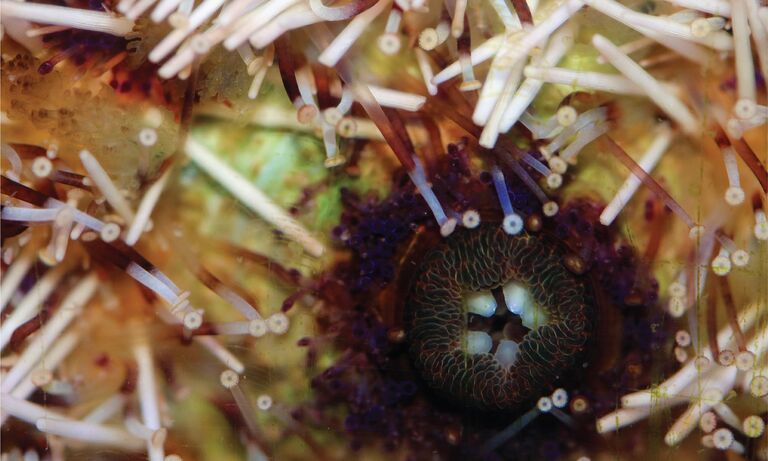

Sea urchins’ bodies are covered in tube feet, small tentacles with cup-like ends that can extend beyond their spines to move along the sea floor, climb obstacles and even roll over if they are flipped. The tube feet are entirely hydraulic, extending and retracting as sea urchins pump water in and out of them. The tube feet double as lungs, a vital part of the water vascular system, absorbing oxygen for respiration and calcium carbonate to build the shell. The suction cups on the ends of the tube feet are called podia, which sea urchins manipulate to sense chemicals in their surroundings and grab useful items, such as food or rock for armour. The Cape sea urchin uses “nippers” or small, pincer-like feet to grip various objects, which are used as sun shields and camouflage.Teeth

On the underside of a sea urchin lies a central mouth with five strong teeth called pyramids. These teeth are connected to a series of complex muscles that allow the sea urchin to chew, grind, grasp, scrape and tear. Several species’ teeth are so strong that they can even burrow into rock with these pyramids. The entire mouth structure is called Aristotle’s Lantern, after the philosopher who was one of the first people to write about sea urchin anatomy. Although powerful and fearsome looking, sea urchins primarily use their mouths to feed on seaweed and other algae.Sieve plate

The sieve plate, or madreporite, is a porous patch close to the anus of the sea urchin. Although these animals have many other openings that take in water, sieve plates are vital for all echinoderms as they transport and filter water for the animal’s central water vascular system. This system controls all the hydraulic organs of the urchin, allowing them to breathe, eat, move and defecate. All echinoderms have open circulatory systems, meaning that the insides of their bodies are open to the seawater around them. By taking water in through the sieve plate and maintaining their internal water pressure, they can create something similar to a small water current inside their bodies.Armoured plates

Sea urchins’ shells are surprisingly complex. The shell, called a test, is divided into five segments, which radiate away from the anus. These segments are each formed by the fusing of four plates, giving the urchin a total of 20 armoured plates.Lips

Sea urchins’ mouths are surrounded by soft lips, which contain small pieces of bone. These lips protect the five gill openings around the mouth while the sea urchin is eating. They are also surrounded by several smaller tube feet which have the sole function of funnelling food morsels into the mouth.Spines

Sea urchins are famous for their sharp spines of all thicknesses, lengths and strengths. Most remarkably, these spines are attached to the sea urchin by a ball joint, allowing them to be pointed in any direction. If a sea urchin is touched unexpectedly, all spines will reorient themselves to point towards the source of touch. These spines are not only for protection but also play a role in navigation, as sea urchins do not have eyes. These animals rely almost entirely on the fact that the skin on their armoured plates is light-sensitive enough to “see” dark patches that could indicate seaweed or a sheltered cave to lie in. This low-resolution vision makes navigation very difficult for sea urchins, especially when the lighting contrast in their environment is lacking. By pointing their spines in one direction and slowly moving them, sea urchins can sense the direction from which light is coming.

Fun facts about microscopic life

- Many small marine animals are fascinating to see under a microscope: a fresh perspective can showcase many interesting adaptations.

- There are around 1 250 species of sea cucumber.

- Many plankton organisms are so small that there are thousands in a single drop of water.

- Plankton absorb carbon dioxide to manufacture their own food and give off 50% of the oxygen needed by animals to breathe back into the atmosphere.

- There are two main types of plankton: phytoplankton, which are plants, and zooplankton, which are animals.

- There are over 2000 known species of nudibranch.

- Mussel is the common name used for members of several families of bivalve molluscs.

- Some sea cucumbers use their own bodies as a defence mechanism by forcing a few internal organs out of their anus. These are quickly regenerated.

Look closer: Nudibranchs

What is a nudibranch?

Nudibranchs, often referred to as “nudies”, are shell-less molluscs and a part of the sea cucumber family. They bear an incredible variety of shapes, colours and patterns to match their surroundings. There are more than 2 000 known species of nudibranchs, most of which are abundant in shallow, tropical waters. Their scientific name, Nudibranchia, means “naked gills” and describes the feathery gills and horns that most have on their backs. Nudibranchs range in size from 0.6 cm to 30 cm.Habitats and Lifestyles

Nudibranchs are carnivores that slowly graze on algae, sponges, anemones, corals, barnacles, and even other nudibranchs. They identify prey using tentacles (called rhinophores) on the top of their heads. Nudibranchs actually get their colouring from the food they eat, allowing them to camouflage. Some even retain their prey’s poison and excrete them as a defence against predators. They are simultaneous hermaphrodites, meaning they can mate with any other mature member of their species. Nudibranchs’ lifespans vary widely, with some living less than a month while others can live for up to a year.